Why do we often say that “Movement is Life”?

Have you ever heard the sentence “movement is life” and wondered why or how?

Some people might think that it is logical without looking for an explanation, some others will be sceptical, thinking that they usually get injured because of specific movements.

Today, we will review the how, and also explain the distinction between the healthy and the injury-prone mobilisation of our joints, and various treatment methods.

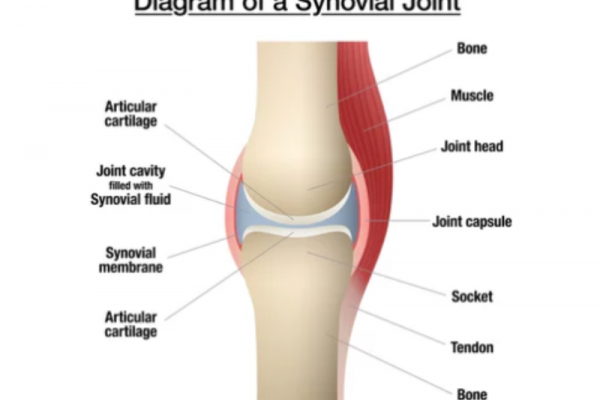

Our body has the ability to achieve smooth movement like a well-oiled machine thanks to a liquid present in our joints: the synovial fluid. The cartilage present at the surface of our bones making up our joints is filled with it, representing 80% of the cartilage volume. This fluid plays an essential role in lubricating joints and therefore, supporting weight.

Diagram of a Synovial Joint

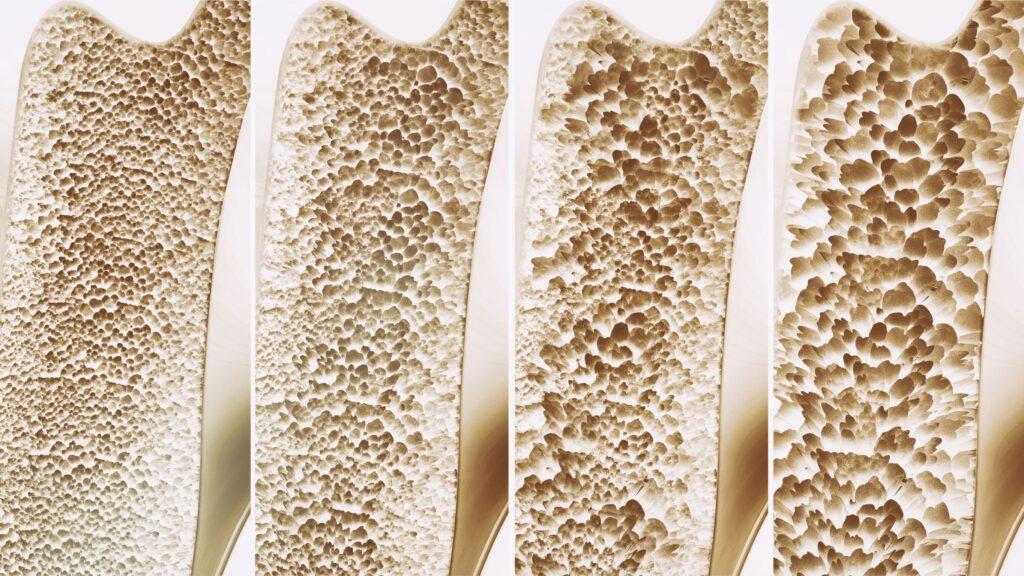

It is important to note that cartilage is porous, so our synovial fluid leaks out of its holes every day. Continuous loss of the fluid leads to considerable decrease in cartilage thickness, and therefore an increase in friction between joint surfaces. The loss of cartilage through this friction can lead to Osteoarthritis, the most common type of arthritis. To illustrate, picture a tire with holes letting air escape; it would lose pressure and no longer be able to support the weight of the car. Cartilage works the same way- once fluid flows out of it, it can’t support load anymore. (Davide Burris, Mechanical engineer, U. of Delaware).

Therefore, the question remains:

How do we drive fluid back into the cartilage?

Let’s use our tire analogy again, but this time, the car is driving on a wet road. Pressure (hydrodynamic) accumulates as water is squeezed into the gap located in between the road and the tire. As the speed increases, pressure builds up within the tire and can fully support the weight of the car at some point. The car is more or less physically “gliding”, or hydroplaning.

Now back to our cartilage being porous, researchers have found that a superior speed of movement is needed for the same phenomenon to occur with the synovial fluid in our joints. In a research focused on knee joints, it was calculated that at a sliding speed of 60 millimetres per second, the synovial was not leaking out and had the capacity to support our weight. That sliding speed more or less corresponds to our normal, walking pattern.

With this understanding and additional studies, researchers have been able to prove that physical activity is not necessarily injurious, and to the contrary, the more active you are the more you will decrease the risks of Osteoarthritis.

These results can help us change our perception concerning the approach of dealing with our bodily pain, and the adaptation of our physical activity management. However, if you are not sure about the nature of your symptoms, it is important to screen them by a medical manual therapist.

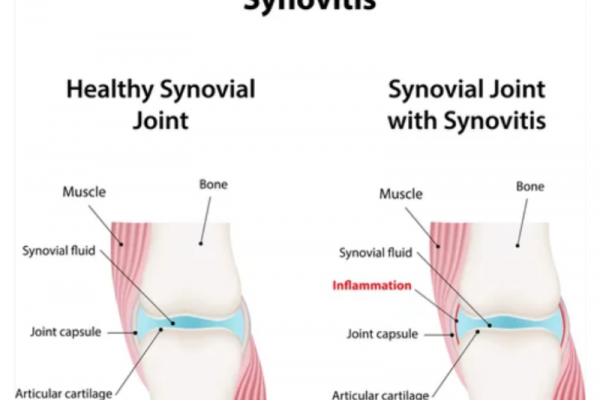

Beyond the above reason of a lack of basic physical activity, joint aches can also be due to an isolated inflammation of the synovial fluid.

This process, Synovitis, can often be triggered in healthy, active persons who are subject to repetitive movements such as fitness exercise (squats, shoulder/chest presses, etc.).

An active individual can also develop such symptoms if he has an unbalanced pelvis, increasing weight bearing on one leg more than another (to be diagnosed by a medical manual therapist).

This kind of overload process is also regularly triggered in overweight individuals. Both cases might show swelling of the joint depending on the severity of the fluid inflammation.

Diagram of a Healthy Knee Joint vs. Knee Synovitis

Regarding the treatment of Synovitis, manual therapy is needed to increase the spaces in the joint capsule in order to relieve the inflammation. Therapy also allows the balancing of weight bearing asymmetries through structural reorganisation and adaptation. Anti-inflammatory drugs will help to decrease painful symptoms, however, they are only a short-term fix and will not lead to recovery in most cases.

The manual practitioner will aim to achieve long-term adaptation by inhibiting or completely getting rid of the predisposing factors of injury or aggravation. His clinical judgement will allow adapted management. Acute phases of inflammation for example will be approached probably first with work on soft tissues such as muscle fibres and tendons surrounding the joint in order to release pressure. Connective tissues such as ligaments and cartilage will also eventually be manipulated through mobilisation techniques: articulation of the joint in its ranges to relieve the capsule’s inflammation and start to restore normal functions of the joints by resetting normality. Stronger manipulations such as HVTs (High Velocity/Low Amplitude Thrusts) that you might associate with “cracking techniques” are also considered to treat dysfunctional joints.

Many factors obviously come to define clinical management. The manual practitioner will adapt specifically to the injury, his/her patient, and the health history. Hence why it is also important for you to share your understanding of your current pain so it can be better explained to you by your therapist.

References

- David Burris, University of Delaware

- Daniele Dini, Tribologist, Imperial College London

- Charles Q. Choi, Scientific NY Times

Written By

Judith Anne Gould

BPhty (Hons) (AUS) | MPhil (HK) Registered Physiotherapist (HK & AUS)

Judith has spent the last 25 of her 35 year physiotherapy career focussing on the assessment and treatment of dysfunctional posture and movement patterns through rehabilitation exercise and ergonomic intervention.